MILANO-SANREMO 1910

What makes a legend in cycling? What makes one race stand out, and grow into a monument? For Milano - Sanremo the legend was born early. This is the story of the fourth edition, the hardest race ever fought.

We are taking a long step back in cycling history for this tale. It’s Sunday the 3rd of April 1910, and we’re taking to the start line on the outskirts of Milano. The weather leading up to the race has been harsh, cold, and wet. In fact, only 71 out of 256 registered riders even bother to take to the line. And when news of snowfall on the route reaches the peloton as they roll out, another eight riders decide to stay behind.

This is how we get 63 riders racing towards the Riviera on this grim Sunday. Ahead lies the traditional route, almost as straight as a crow flies from the industrial capital Milano to the swanky seaside resort town of Sanremo.

As of today, just shy of 300 kilometers of route. And even though this is road racing in its infancy, the bikes and kit wouldn’t be wholly unfamiliar to us. The bikes are drop bars, with freewheels, some have coaster rear brakes, and they weigh around 12 kg. Where we today equip riders with lycra, chamois, and maybe best of all: GoreTex. Riders in 1910 must make due with knit wool jerseys, cotton shorts, and leather saddles.

We are taking a long step back in cycling history for this tale. It’s Sunday the 3rd of April 1910, and we’re taking to the start line on the outskirts of Milano. The weather leading up to the race has been harsh, cold, and wet. In fact, only 71 out of 256 registered riders even bother to take to the line. And when news of snowfall on the route reaches the peloton as they roll out, another eight riders decide to stay behind.

This is how we get 63 riders racing towards the Riviera on this grim Sunday. Ahead lies the traditional route, almost as straight as a crow flies from the industrial capital Milano to the swanky seaside resort town of Sanremo.

As of today, just shy of 300 kilometers of route. And even though this is road racing in its infancy, the bikes and kit wouldn’t be wholly unfamiliar to us. The bikes are drop bars, with freewheels, some have coaster rear brakes, and they weigh around 12 kg. Where we today equip riders with lycra, chamois, and maybe best of all: GoreTex. Riders in 1910 must make due with knit wool jerseys, cotton shorts, and leather saddles.

The peloton of today makes light work of the first couple of hundred kilometers of the route. Most team leaders are tucked deep inside the group, sheltered and well dressed. But remember, we are in 1910, the roads are rough, and the weather has turned them even rougher.

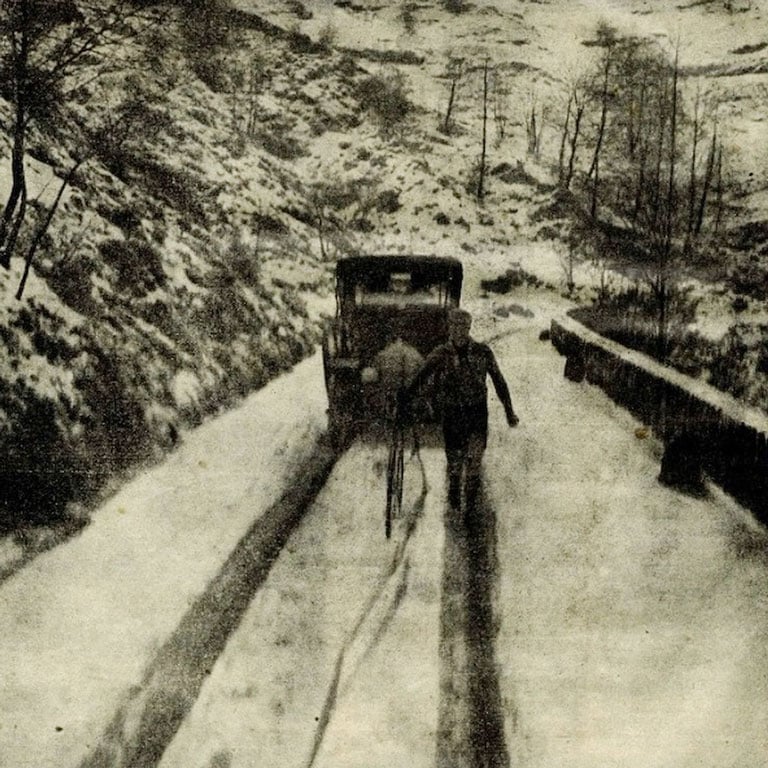

Il Passo Turchino, although 26 kilometers long, only rises a little more than 500 meters. However, even today Turchino might throw a spanner in the cogs of the race. Some might remember the snowfall in the 2013 edition, where riders had to be shuttled under the pass in buses, and in 2020 it had to be taken out due to rockfalls and damaged roads. But in 1910, there are no buses to save the riders.

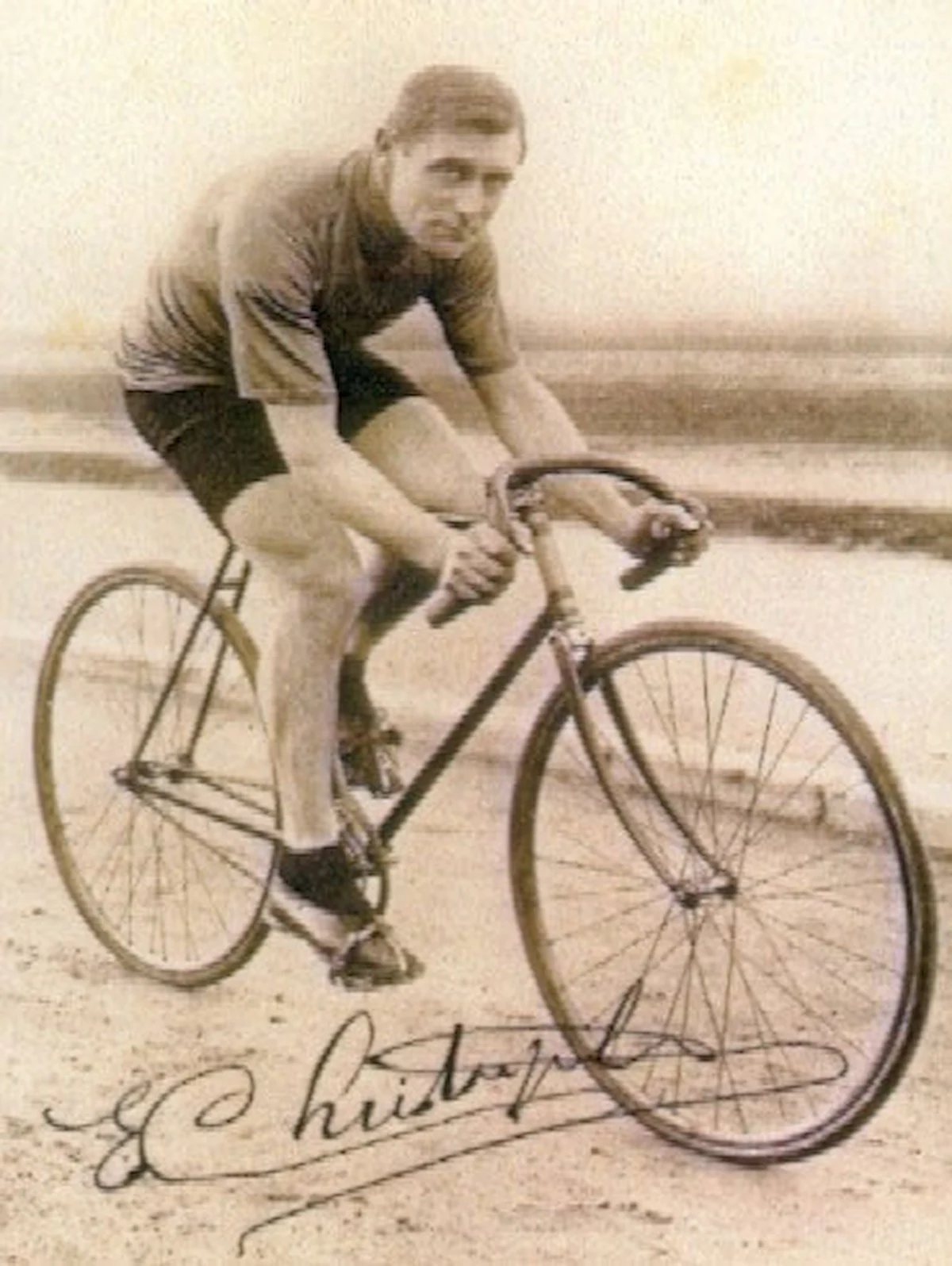

At the foot of Turchino the Flemish rider and hardman Cyrille Van Hauwaert has a three-minute lead. Hunting him is a group of three Italian riders, with Luigi Ganna as the big star. Ten minutes in arrears comes French rider Eugene Christophe, the hero of our story, and of so many other good stories. Christophe rides with his team-mate and compatriot Ernest Paul. They are riding their own pace up the pass. Somewhere on the climb, Paul is lost, and Christophe passes Luigi Ganna.

Il Passo Turchino, although 26 kilometers long, only rises a little more than 500 meters. However, even today Turchino might throw a spanner in the cogs of the race. Some might remember the snowfall in the 2013 edition, where riders had to be shuttled under the pass in buses, and in 2020 it had to be taken out due to rockfalls and damaged roads. But in 1910, there are no buses to save the riders.

At the foot of Turchino the Flemish rider and hardman Cyrille Van Hauwaert has a three-minute lead. Hunting him is a group of three Italian riders, with Luigi Ganna as the big star. Ten minutes in arrears comes French rider Eugene Christophe, the hero of our story, and of so many other good stories. Christophe rides with his team-mate and compatriot Ernest Paul. They are riding their own pace up the pass. Somewhere on the climb, Paul is lost, and Christophe passes Luigi Ganna.

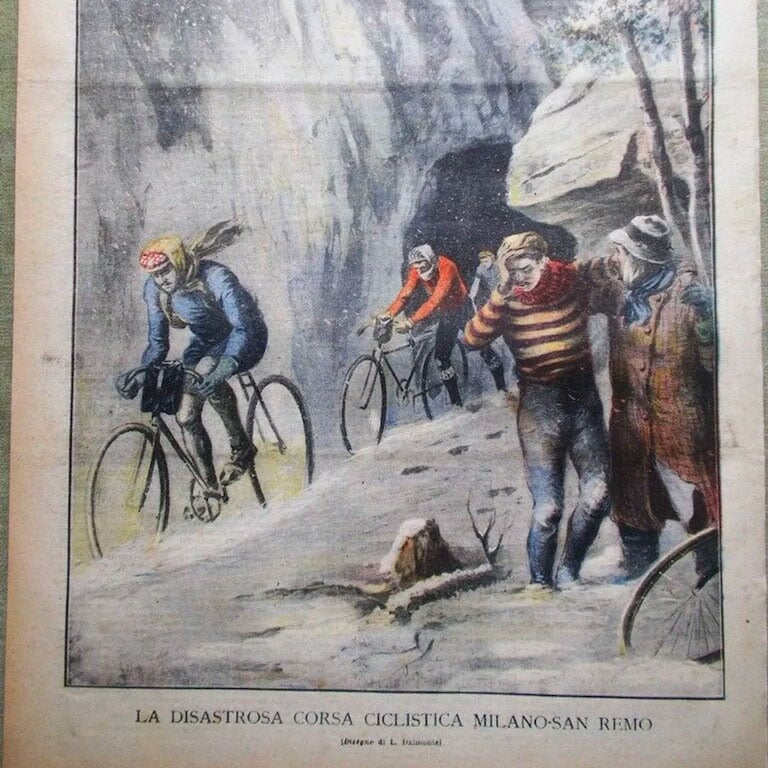

This story has been told and re-told countless times since 1910. Splits and differences are a little hard to come by. So excuse the lack of exact detail. But somewhere near the top of the pass Eugene Christophe has to seek shelter from the weather in an abandoned railway tunnel. The bad weather has turned worse, and there’s a blizzard on the slopes of Passo Turchino.

In the same tunnel, alone soigneur is stationed. Christophe asks if the soigneur knows the standing, he raises six fingers. Christophe interprets this as being six minutes behind the leader if only to lift his spirits. Had it meant that he was in the sixth rank, he would be too far behind. Christophe was, like many of our current hardmen, from a cyclocross background, he is used to cold weather, but this is extreme.

Pushing and carrying his bike over the crest of Turchino, he is probably about ten minutes behind sole leader Van Hauwaert. Hauwaert has later said that he passed two skiers on the way up, the conditions were brutal!

In the same tunnel, alone soigneur is stationed. Christophe asks if the soigneur knows the standing, he raises six fingers. Christophe interprets this as being six minutes behind the leader if only to lift his spirits. Had it meant that he was in the sixth rank, he would be too far behind. Christophe was, like many of our current hardmen, from a cyclocross background, he is used to cold weather, but this is extreme.

Pushing and carrying his bike over the crest of Turchino, he is probably about ten minutes behind sole leader Van Hauwaert. Hauwaert has later said that he passed two skiers on the way up, the conditions were brutal!

It is already five hours since they left Milano, they are still less than halfway to San Remo. Although the descent from Turchino is much steeper than the ascent, the snow is much too deep now. Tales differ, as they often do, some say twenty centimeters of snow, others say forty. Van Hauwaert, himself a previous winner of the race, loses control and takes a heavy fall, he is overtaken by Christophe.

Coming down the slopes, a local innkeeper decides this madness can’t go on. He promptly orders Christophe, now leader of the race, Van Hauwaert, and later the re-emerged Ernest Paul into his chalet. The three men are all team-mates at Alcyon-Dunlop, but at this point, it’s every man for himself. While trying to regain some heat, Christophe takes a seat by the window, keeping a watchful eye on the road for competitors.

Van Hauwaert on the other hand has had enough, he decides to take the innkeeper up on his offer of food and drinks. The large Belgian, nicknamed The Wolf of Flanders, digs into food and wine in the refuge. But Christophe sees four riders pass, for him the race is still on!

Coming down the slopes, a local innkeeper decides this madness can’t go on. He promptly orders Christophe, now leader of the race, Van Hauwaert, and later the re-emerged Ernest Paul into his chalet. The three men are all team-mates at Alcyon-Dunlop, but at this point, it’s every man for himself. While trying to regain some heat, Christophe takes a seat by the window, keeping a watchful eye on the road for competitors.

Van Hauwaert on the other hand has had enough, he decides to take the innkeeper up on his offer of food and drinks. The large Belgian, nicknamed The Wolf of Flanders, digs into food and wine in the refuge. But Christophe sees four riders pass, for him the race is still on!

In Christophe’s own words:

“

I saw four riders go by, or at least four piles of mud. I decided to press on.

Promising the innkeeper that he is only leaving to seek medical attention on the lower slopes he slips back out into the snow. Descending, Christophe gets word that at least Luigi Ganna is in the group ahead. He is also told that Ganna has been seen hitching a lift on a team car over the pass. As he catches up to the group it becomes clear that these riders are in a bad shape, Christophe promptly passes them. In doing so, the group splits up in pursuit, there are five solo riders chasing towards the coast.

In Savona, Christophe has a lead of fifteen minutes on Ganna, and it’s growing rapidly. Starting to feel confident, Christophe even pauses for dinner and a change of bike. The weather is still atrocious, rain, hail and cold weather batter the remaining riders, probably less than ten at this point.

The modern run-in to Sanremo follows the coastal road and takes detours up some climbs in the final. But in 1910, the road runs up and down the coastal climbs all the time. The weather has washed away all markings, and Christophe has no idea of the route ahead. At one point a local cyclist guides him along for a portion of the route, but he is unsure if he has followed the right path to the finish.

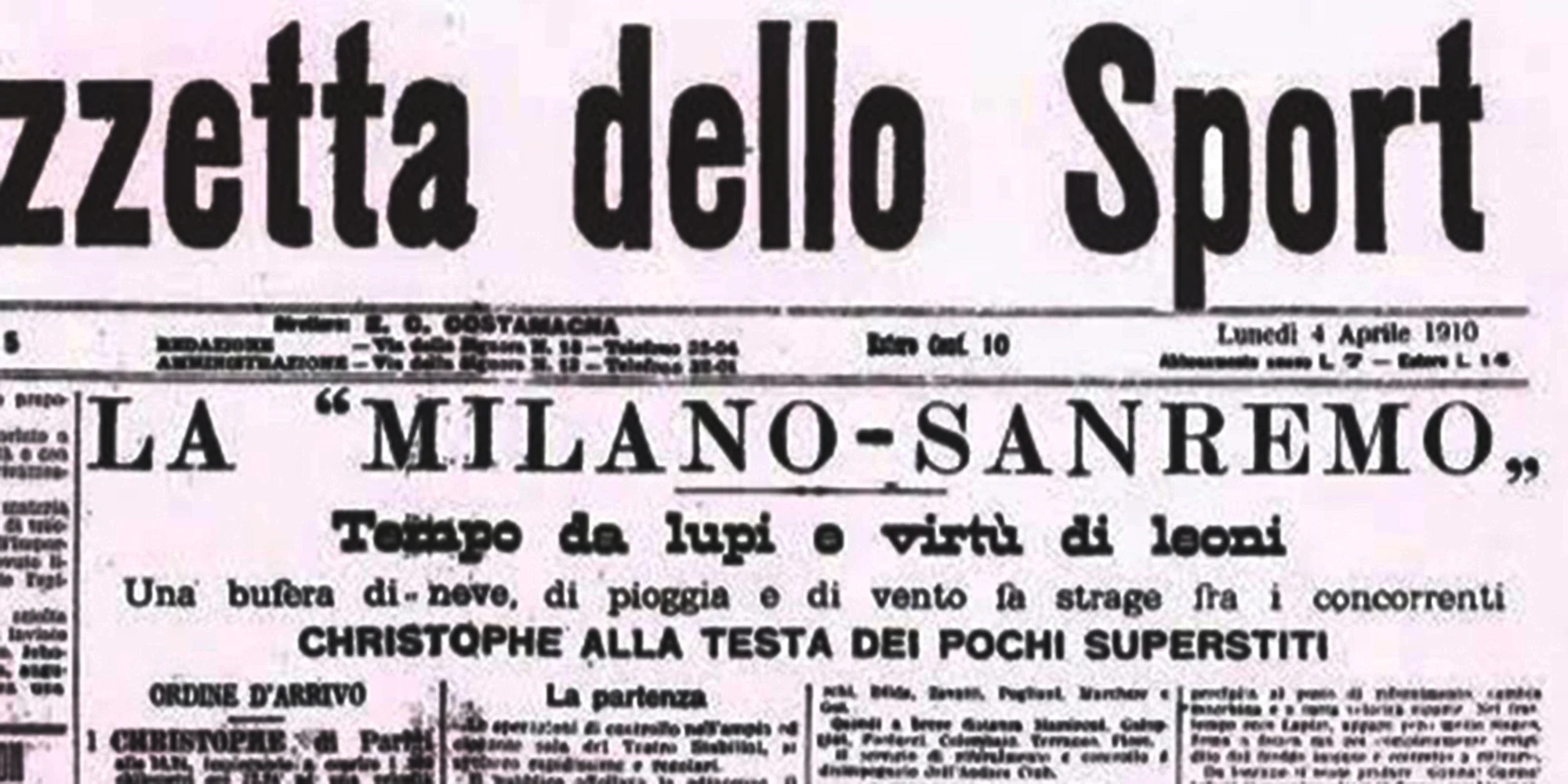

Whatever the route, he finishes on la Via Roma in Sanremo after 12 hours and 24 minutes of racing. To date, the average speed of 23.31 kph is the slowest speed recorded for any Monuments race. 39 minutes behind him, Luigi Ganna finishes, but he is disqualified for riding on his team car through the snow.

Three more riders reach Sanremo before the cut-off, the last finishing 2 hours and 6 minutes behind Christophe. Reports also list two more finishing outside the cut-off, so a total of seven riders finish the distance. Imagine their exhaustion?!

In Savona, Christophe has a lead of fifteen minutes on Ganna, and it’s growing rapidly. Starting to feel confident, Christophe even pauses for dinner and a change of bike. The weather is still atrocious, rain, hail and cold weather batter the remaining riders, probably less than ten at this point.

The modern run-in to Sanremo follows the coastal road and takes detours up some climbs in the final. But in 1910, the road runs up and down the coastal climbs all the time. The weather has washed away all markings, and Christophe has no idea of the route ahead. At one point a local cyclist guides him along for a portion of the route, but he is unsure if he has followed the right path to the finish.

Whatever the route, he finishes on la Via Roma in Sanremo after 12 hours and 24 minutes of racing. To date, the average speed of 23.31 kph is the slowest speed recorded for any Monuments race. 39 minutes behind him, Luigi Ganna finishes, but he is disqualified for riding on his team car through the snow.

Three more riders reach Sanremo before the cut-off, the last finishing 2 hours and 6 minutes behind Christophe. Reports also list two more finishing outside the cut-off, so a total of seven riders finish the distance. Imagine their exhaustion?!

Up to this point the story is based on reputable sources, Eugene Christophe himself wrote detailed reports from his efforts. So the aftermath is pretty well established. Christophe was hospitalised after his victory, with frostbite and severe exhaustion. He was nursed at the hospital for a month, and didn’t return to full health for another six months. It took almost two years until his next road victory.

But, let’s not have the truth get in the way of a good story. The legend tells that when Christophe arrived in Sanremo to an empty town, nobody was expecting any finishers. To regain his heat and energy he entered the nearest cafe and ordered something strong and hot. This is a man in his prime, he has conquered the hardest race to date, and probably the hardest race of all time.

To this day the jersey is said to hang in a small attic room in Sanremo, a memento from The hardest race.

But, let’s not have the truth get in the way of a good story. The legend tells that when Christophe arrived in Sanremo to an empty town, nobody was expecting any finishers. To regain his heat and energy he entered the nearest cafe and ordered something strong and hot. This is a man in his prime, he has conquered the hardest race to date, and probably the hardest race of all time.

To this day the jersey is said to hang in a small attic room in Sanremo, a memento from The hardest race.

FOOTNOTES

Words by Lars Blesvik. Images: bdc-mag.com, RCS, Bibliothèque National de la France

Words by Lars Blesvik. Images: bdc-mag.com, RCS, Bibliothèque National de la France